Introduction

The Flowering Tree of Gekken is a treatise on shinai and bogu practice, written in 1855 by one Tsutsui Rokka. Tsutsui was a student of Shirai Toru, a renowned teacher of martial arts whose name is still well-known today. Shirai was the second-generation head of Tenshin Itto-ryu (also known as Tenshinden Itto-ryu), although he had originally studied Ono-ha Itto-ryu under Nakanishi Chuta Tsuguhiro. Another student of Tsuguhiro, Terada Goroemon Muneari, was the founder of Tenshin Itto-ryu, which was based very closely on Ono-ha Itto-ryu as transmitted by the Nakanishi line. However, although Nakanishi Chuzo Tsugutake had introduced shinai and bogu training to Itto-ryu a generation previously, Terada completely eschewed shinai keiko, choosing only to practice kata. This was seen as quite unusual – and perhaps old-fashioned – behaviour at the time. In spite of this, Terada was said to be one of the dojo’s strongest swordsmen. There is a story of how he was once challenged to a shinai match and, despite refusing to wear bogu and choosing to use his relatively short bokuto instead of a shinai, he countered all his opponent’s attacks and soundly defeated him.

However, Tsutsui states clearly in The Flowering Tree of Gekken that he began shinai and bogu training (at the time known as gekken or gekiken) at Shirai Toru’s dojo. Therefore it seems that unlike Terada, Shirai took part in shinai keiko, or at the very least had his students practice it.

The cover of the original document is marked with a warning that it is only to be read by students of Tenshinkan Dojo. It is not clear precisely where and when Tenshinkan was established, but it is thought to have been located at Tenma in Osaka. During the early 19th century, Terada Muneari spent time in Osaka in the employ of Matsudaira Terunobu. It has been postulated that Tenshinkan dojo may have been founded during this period.

To place this text in its historical context, it was written in a period when shinai and bogu keiko had become the norm for most dojo. Some traditionalists were rather concerned about what they saw as incorrect approaches to swordsmanship that were manifesting themselves in gekken (see also Nakanishi Tanemasa’s comments in the Itto-ryu Book of Oral Recollections). Very long shinai, poor reigi and techniques that would not work with a real sword were on the rise and Tsutsui attempts to address these in the text, through implementations of Itto-ryu technique and strategy.

Overall, The Flowering Tree of Gekken is a brief but valuable record from a turbulent period in kendo’s history, and offers insight into the early evolution of the art. I have translated it in two parts, the first of which is below.

The Flowering Tree of Gekken¹

Tsutsui Rokka

For members of Tenshinkan Dojo only. Not to be shown to outsiders.

Over forty years ago, when I was still young, I entered Shirai Tōru sensei’s dojo, donned an iron men, kote and a stomach wrap², took up a shinai and began my study of gekken. Recently however, there is a trend for people to use very long shinai with narrow tips³, and the wearing of a basket of thin bamboo strips instead of an iron men has become very common. People are also using utterly despicable technique. Over my forty-odd years of training, many changes have taken place leading up to this point, and before long it is inevitable that a complete revolution in gekken must take place.

In advance of this, we must take the lead amongst swordsmanship schools and oppose the current trend of despicable technique. To this end, I submit for the esteemed criticism of my learned friends the following record of techniques for certain victory in gekken, and a critical discussion of the differences between the old and new styles.

¹ The Japanese title is Gekken Naniwa no Ume (撃劔難波乃楳), meaning literally “The Naniwa Plum Blossom of Gekken.” This is a reference to the plum blossom in the Naniwa area (in and around present-day Osaka), which was famed for its beauty and aroma and was seen as the herald of spring. According to legend, in around the 5th Century AD the Emperor Nintoku loved the beautiful plum blossom trees of Naniwa so much he had them uprooted and moved to the capital. Henceforth however, the trees only sprouted blossom on the branches that were pointing towards Naniwa. After they were returned to their original location, they blossomed fully and fragrantly once more. With this title, Tsutsui seems to be suggesting that gekken must be done in accordance with this text in order to be in “full bloom,” and that straying from the source will lead to hollow and lifeless practice. It may also be a reference to the famed plum blossom of the area in which Tenshinkan dojo is thought to have been located.

² The do was not used by all schools at this point. The shihan of another famous fencing school of the period, Saito Yakuro of Shindo Munen ryu, only introduced the use of do to his school after he was injured in a bout with Chiba Eijiro of Hokushin Itto-ryu. Although Saito wore a padded wrap around his torso, Chiba, whose school already used the do, struck Saito repeatedly in his flanks, leaving him covered in bruises. After their match, Saito concluded that he could not continue to practise gekken without wearing a do, and introduced their use to his dojo.

³ A famous gekken practitioner of the period was Oishi Tanetsugu (1797-1863) of the Oishi Shinkage ryu. He was very tall and used a shinai 5 shaku 3 sun (approx. 160cm) in length. He was known for his katate-tsuki and for challenging well-known swordsmen and dojo in Edo. He had a great deal of success in his challenges and is often cited as the reason for the popularity of extremely long shinai during the 19th century.

On Shinai

The shinai should be 2 shaku 5 sun in length, with a tsuka of no longer than 1 shaku⁴. The tsuka should be held with a supple grip, with a gap of 5 or 6 bu (approx. 1.5-1.8cm) between the kote and the tsuba. The end of the tsuka should be held inside the palm of the left hand.

The reason for not favouring a long sword is because it is disadvantageous at close range. Keeping a gap between your kote and the tsuba prevents the sword becoming stiff and lets you move freely. Holding the end of the tsuka inside your hand allows you to press your palm against it when thrusting.

One school of thought says that without a long sword you cannot reach your opponent, so not using one puts you at a major disadvantage. If that were true, in a fight with real swords, when facing an opponent with a sword 5 or 6 sun (15-18cm) longer than yours, you would have no recourse but to run away. However, in swordsmanship there is no distinction between long and short. One should simply use one’s weapon adaptively to ensure victory over one’s opponent. Even those who should know better argue shamelessly that a long weapon is necessary. What utter nonsense this is! When I hear this argument, I cannot help but laugh.

⁴ Approximately 76cm, with a tsuka of approximately 30cm. A modern kendo shinai is 3 shaku 9 sun or 3 shaku 8 sun in total – around 9-12cm longer than what is prescribed here.

Posture and Attitude

When engaging in gekken practice in the dojo, civility should be strictly maintained. Your consciousness must be placed in the lower abdomen below the navel. You should sink your posture to be closer to the ground⁵, stretch the abdominal muscles⁶ and put power strongly into your hips. You should move forward with your right foot stepping very lightly on the ground. If you do not practice in this manner, it will be hard to move back and forth and left and right freely and flexibly. Also, if you do not make your hands very supple, your strikes and thrusts will not have any reach. Without practising in the above manner, your posture will fail and you will not be able to move freely.

When you stamp your right foot hard on the ground, you are not allowing yourself to be governed by free will.⁷

⁵ The original text reads literally, “make yourself short.” This is in contrast to modern kendo, where people are encouraged to make themselves tall, and probably reflects the fact that kendo has evolved into a more athletic style that is less concerned with cutting as if the shinai is a real sword. In surviving densho of Tenshin Itto-ryu, diagrams of kamae show postures with the knees bent and the hips sunk low.

⁶ This suggests pushing out the lower abdomen.

⁷ In other words, stamping hard commits you to your action and for a moment stops you from moving freely in any direction.

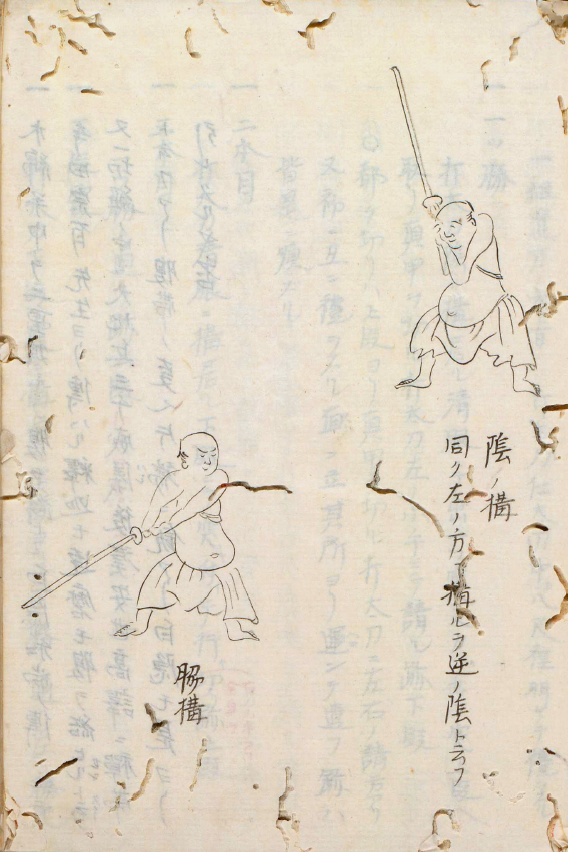

Clik here to view.

Kamae diagrams in Tenshin Itto ryu densho

Awareness

You must remain constantly aware of your opponent’s eyes and the tip of your sword. Do not allow yourself to forget these things even for a moment.

Being aware of the tip of the shinai prevents the weapon from being lifeless and makes it easy to perform techniques at blinding speed. Also, if you are not constantly aware of your opponent’s eyes, it is very hard to read his intentions. Without reading his intentions, it is difficult to perform techniques with go no sen.

The preceding points are absolutely vital in gekken. However they are not things you will immediately be able to do.

On Speed

Speed is of great importance to physical technique. When you sense your opponent is off guard⁸, you should execute your technique at great speed without any hesitation. Other schools’ techniques do not compare to ours. They should be prized highly.

If you are aware that your opponent is not off guard, you may yet be able to strike him if you attack him with powerfully.

In a well-matched, close fight, you should not make dirty or vulgar attacks. Without watching your opponent’s sword, you should place your full awareness in his eyes. When he thinks to attack you, this will show in his eyes. When he thinks to attack, there will be movement of his mind, so you can take advantage of this opportunity and strike him with go no sen.

When you have effected a good defence, and your opponent is not striking at you, you should throw out a strike or thrust and make his mind move. Or, you should relax your defence where you want him to strike, thus causing him to attack, whereupon you can follow with your own technique.

⁸ Kyo (虚), literally “falsehood,” indicating gaps in kamae (suki) or a lapse in attention.

Countering Men

When your opponent comes to strike your men, you should counter with suriage and immediately strike him. It is possible to counter with a hari⁹ to the side and follow with a strike, but this is not as good as doing suriage. Naturally, when doing suriage, you should pull your right foot back slightly. This gives you some flexibility in which to perform the waza. Moreover, blocking a strike before returning with a strike of your own is too slow and should be avoided.

When you perform suriage or hari on your right side (i.e. omote, using the left shinogi), when your shinai comes into contact with your opponent’s you should step in and towards your opponent’s right with your right foot to strike. When performing suriage or hari on your left (i.e. ura, using the right shinogi), you should step forward and to the opponent’s left with your right foot. When you step in, depending on whether you are on the left or right of your opponent’s sword you should open up your body a little to the left or right accordingly, and strike your opponent’s men or kote before adopting Myoken¹⁰.

⁹ Slapping the opponent’s shinai aside.

¹⁰ Myoken is one of the highest teachings of Itto-ryu, and is the first technique of the Kojo Gokui Goten. In very basic terms it is a kind of harai-otoshi-tsuki, but the timing, distancing and execution of the technique itself are extremely difficult. Furthermore, the feeling of the waza is very important – it must be performed with no thought, from seemingly nowhere, and have no definite beginning or end. In the above text, it is difficult to tell exactly how Tsutsui wished students to use the technique, but it appears to form a kind of zanshin action where the practitioner breaks through the opponent’s defence to end with his weapon pointed squarely at their centre.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Countering Do

When your opponent comes to strike your right do, you should step forwards and to his right flank with your right foot, and keeping close to his body, circle around him to his rear. If he comes to strike your left do, you should step forwards and to his left flank with your right foot, and keeping close to his body, circle around him to his rear. When you circle close to your opponent, he will not be able to use his sword freely. You should then adopt Myoken to suppress him.

Also, when your opponent comes to strike your right do, you should step back with your right foot while adopting wakigamae¹¹, then while moving backwards strike his left or right kote¹². It is difficult to strike men from this position. In situations like this, a long sword is extremely unwieldy.

¹¹ In Itto-ryu, wakigamae has the sword held at your flank rather behind you – in this case it is held in a position to intercept the incoming do strike.

¹² Depending upon which target is open.

To be continued in Part 2.

Sources and further reading:

『日本武道大系 第九巻』 著者:今村嘉雄 (ほか)〈編〉 出版社:同朋舎出版 出版年:1982

『剣道』 著者:高野佐三郎 出版社:兵林舘 出版年:1918

『兵法一刀流』 著者:高野弘正 出版社:講談社 出版年:1985

『一刀流極意』 著者:笹森順造 出版社:「一刀流極意」刊行会 出版年:1965

『剣道五百年史』 著者:富永堅吾 出版社:百泉書房 出版年:1972

『撃剣柔術指南』 著者:米岡稔 出版社:東京図書出版 出版年:1897