This series of articles presents what I believe to be the first-ever English translation of the 19th Century Ittō-ryū Book of Oral Recollections (Ittō-ryū Kikigaki, 一刀流聞書). Based on the teachings of Nakanishi Tanemasa, a hugely influential swordsman of his era, this text covers technique and philosophy of the Ittō-ryū school of kenjutsu as well as Nakanishi’s own opinions. The text highlights many significant links between Ittō-ryū and modern kendo, and is still highly relevant to kendo practitioners today.

Parts one, two and three of this series are already available, and the translation concludes with part four below. Thank you for reading.

Tachiumare

Tachiumare [lit. the birth/origin of a sword strike]* is explained as follows. Put simply, in today’s shiai, when facing off with your opponent or dealing with them, both parties’ swords cannot be said to be tense: they are only waiting. When your opponent intends to strike, their sword tip will tense up and become firm. This is the moment at which they will strike. Knowing this, you should wait within attacking, and attack within waiting. This is known as ken-chū-tai, tai-chū-ken (懸中待 待中懸)**. The key point is where the sword of the opponent rises or falls and becomes tense. When the opponent intends to strike he will raise his sword tip slightly. When he intends to thrust he will lower his sword tip slightly. From this, you can understand tachiumare. If you understand the above and put it to use, you should progress until you naturally understand the point of respiration (kokyū).

*Tachiumare is an important Ittō-ryū teaching which appears, in different forms, in both the Kanaji Mokuroku and the Hon Mokuroku, the second and third tiers of transmission respectively.

**This teaching also appears in the Hon Mokuroku.

During shiai

In shiai, the mind is false but the shinai is truthful (if the mind is false, the truth will be apparent through the techniques on the surface). This is because the shinai is always poised to immediately cut or thrust.

This is one case where, while maintaining respect for the [Ittō-ryū] school, it is acceptable to deviate from its teachings. When young, you should regard technique as everything, even to the point of failure. Passing beyond this, when you are over forty years old you should make use of your spirit and presence. In the same way, [young] people do as they please, but as they get older they become more mindful and thrifty.

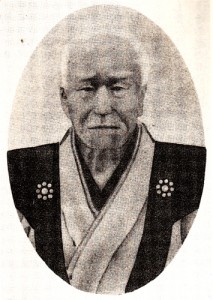

Takayanagi sensei

A man asked Takayanagi*: “Sensei, you say that we must be able to defeat a strong point weakly and a weak point strongly. But what does it mean to win with strength?” Takayanagi replied, “I do not yet know.”

* Takayanagi Matashirō was a student of the third generation headmaster of the Nakanishi line of Ittō-ryū (and Tanemasa’s father), Nakanishi Tanehiro. Takayanagi’s family transmitted a branch of Toda-ryū that came to be known as ‘Takayanagi-ha.’ He was one of the so-called ‘three crows’ of Nakanishi dojo, the other two being Terada Muneari and Shirai Tōru, respectively the first and second-generation headmasters of Tenshin Ittō-ryū. Together these three acted as guardians for the young Nakanishi Tanemasa following Tanehiro’s death. Takayanagi was famous for his ‘silent sword’ technique, where he would defeat opponents without letting their shinai touch his.

![]()

The moon on water

The moon on water is explained as follows. You make yourself like the moon and shine light upon your opponent. Or, if you make yourself as water and allow your opponent to become like the moon, you will see the points where the light they cast is insufficient. In other words, you will realise their areas of falsehood.

Put your feeling into the belly of your opponent and act as if no swords are involved. Allow this to assist your use of the sword.

The ability to fight is something that no-one can teach, but even a child has it. At first, our school teaches sō and gyō [see above] without any connection to fighting, and exclusively teaches to remain calm and suppress the urge to fight. At first, students learn by paying no mind to swords conveying to the opponent their spirit alone. Thus, when they allow this approach to assist their use of the sword they will be able to attain victory.

The nature of a spark

The nature of a spark (sekka no kurai, 石火の位) is the feeling of a sickle striking a stone: it is sharp and fierce. When you and your opponent’s swords meet, the nature of a spark is the moment of sharpness where you transfer your feeling and your sword to the opponent.

Adhere to doctrine

Even if a purse is dirty, you should not throw away the coins it holds. Even if you are of lowly stature, you should not discard propriety and doctrine*.

*The word used here is hō(法). This indicates law, dharma, reason, natural order, propriety and doctrine.

The three natures

The nature of dew (tsuyu no kurai, 露の位), the nature of a spark (sekka no kurai) and the nature of a temple bell (bonshō no kurai, 梵鐘の位) can be understood as follows. With blunted swords (habiki, 刃引) stand far apart from your opponent, calmly and unhurriedly approach them and with a fullness of spirit cut down their sword with kiriotoshi. When you cut down their sword, it is with the nature of dew. When your sword connects with theirs, it is with the nature of a spark. Once you have struck down their sword, immediately you assume the nature of the temple bell, and send out a resounding echo that engulfs your opponent.

The nature of dew (tsuyu no kurai) is like a drop of dew collecting on a leaf. Although it is constantly on the verge of falling from the leaf it hangs on, then plops from the leaf as the tension breaks. Standing away from your opponent, as you approach them you must amass a fullness of spirit, then like a drop of dew falling from a leaf cut down their sword with kiriotoshi. The point of cutting down their sword has the nature of a spark [see above].

![]()

The master and the amateur

A skilled bowman, when using a noisemaker arrow* to exorcise someone possessed by a fox spirit**, stood facing the target with the intent to shoot the shoulder, where the possession was located. As he aimed at the shoulder and went to shoot the swelling, it shifted to the waist. When he aimed at the waist, it shifted elsewhere. As a poor shot would have killed the person, the bowman passed his bow and arrow to his servant and commanded him to shoot, but the servant declined. The command was issued strongly, and the servant reluctantly stepped forward to face the target with an arrow on his bowstring. In that instant the fox possession was dispelled. The master was so skilled he could not miss where he aimed for, but it was impossible to know where the unskilled servant’s arrow would have struck. Thus, the fox spirit took fright, and vanished.

When someone has trained a little with a sword and knows something of kiriotoshi and methods for winning bouts, it is good to engage them. A complete amateur who knows nothing of how to cut with a sword will attack randomly and without logic, and it is not good to engage with them.

*A noisemaker arrow (hikime or kaburaya) refers to a blunt arrow with a conical device fitted at its tip, designed to make a loud noise when shot. These kinds of arrows were used to scare away animals, and presumably, as this tale shows, were also used in exorcism.

**Fox possession (kitsunetsuki, 狐憑き) was a condition believed to affect young women who had been possessed by the spirit of a fox, which was viewed as a supernatural creature in Japanese folklore. Symptoms were varied but often included fox-like behaviour, frothing at the mouth, developing a huge appetite and the presence of a lump under the skin that would shift when touched or pricked with needles. Exorcism usually took place at Shintō shrines. The fox possession myth is to some extent analogous with lycanthropy in European folklore.

![]()

Woman possessed by a fox spirit

Growth and maturation

The three methods shin, gyō and sō* have nothing to do with physical technique, and are methods of the mind. When your technique has matured, your sword, body and mind will be unified.

For example, if you view plum blossom, you may paint a picture of the flowers you see, but you cannot capture their scent. A plum tree draws up moisture from the earth, grows tall, its flowers bloom and its fruit ripens. The painting is lacking the shin of the earth, so it merely looks pleasing to the eye. Swordsmanship too is like a plant growing from the earth. Solid ground, shin, is vital. You cannot train in swordsmanship without a determined focus. You should have a strong appreciation for this.

*Shin, gyō and sō, as explained previously, refer to timings in Ittō-ryū. However their scope is much broader than this. They can also refer to speed, shape or how close a technique is to the basic model, amongst other things. In the above description the meaning is close to that used in calligraphy: shin denotes precise, standard characters, sō very loose, flowing characters, and gyō is somewhere in between. Without learning shin it is not possible to progress to gyō and sō.

Turning the self

“Turning the self” has the following meaning. A lamp that shines its light directly upon you is a hindrance, but if you try to shield yourself from the light, it will still seep through the gaps between your fingers. If you close the lamp’s shutters, the light will still stream through the cracks between them. If you turn so that the lamp is not in front of you but to the side, it becomes an even greater hindrance.

It is best to turn to face away from the light, so you cannot see it at all. You will not be aware that the light is shining upon your back, and will be unperturbed by it. This is what is known as “turning the self.”

Although I know little*, I believe the above description of shielding yourself from light means that if you put yourself through great pains in training the kumitachi, acquiring skill, learning to read the tells in an opponent’s mood and sword movement, and become able to shine your own light on the opponent, you may progress further, to the point of extinguishing your opponent’s light. At this point you will no longer be perturbed by anything.

*This line suggests that this paragraph is written from the perspective of Takano Mitsumasa.

The other side of victory

A die is a cube, with faces numbered one to six. Six is the highest number attainable. When you win totally, the reverse of that victory is a singular defeat of one. When you win with a five, the reverse is two defeats. When you win with a four, the reverse is three defeats. This is the point of life and death.

Note: For clarity’s sake, it should be noted that a die has six and one, five and two and four and three on opposite sides.

Adapting to circumstance

Using the hardness of chopsticks, you can hold the softness of a bean. You do not set out to use the chopsticks stiffly because they are hard, nor softly because the bean is soft. You must use them adaptively, according to circumstance. Swordsmanship is the same.

![]()

Mountain foot, river mouth

At the mountain, its foot. At the river, its mouth.* This means that when you see an opponent intends to thrust at you, you should leave the target of your throat open while protecting all other targets, then defend the throat when he makes his thrust.

If you try to prevent him from making this thrust from the beginning, he will change the target he is attacking. To leave yourself open when the opponent intends to thrust is what is called “mountain foot, river mouth.”

*This phrase appears in the Kanaji Mokuroku.

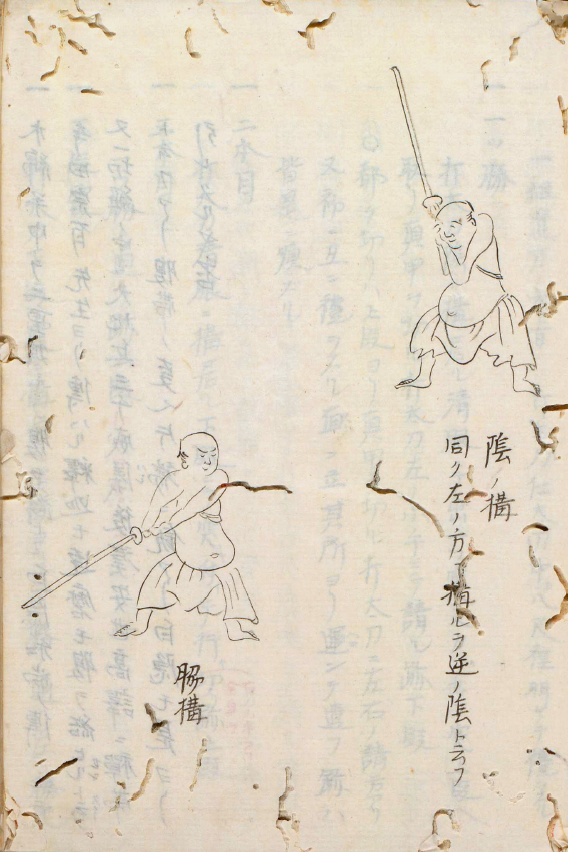

Yin and Yang in Itto-ryu and other schools

Naganuma Jikishinkage-ryū* teaches to use jodan no kamae with the spirit of ‘activeness within activeness’ [yang within yang, 陽中の陽]. Ittō-ryū teaches to use gedan with a spirit of passiveness [yin, 陰]. With a spirit of ‘activeness within activeness,’ if you do not issue forth [i.e. be proactive, attack] then you will fall into passiveness. In our school, when you issue forth the passiveness within your passiveness becomes active, and you are able to apply yourself.

Munen-ryū** takes a position between activeness and passiveness, and utilises a slightly distorted seigan no kamae.

*‘Naganuma’ refers to the main branch of Jikishinkage-ryū swordsmanship. Naganuma Kunigo, the seventh-generation headmaster of Jikishinkage-ryū is credited with introducing practice with shinai and bogu, as pioneered by Nakanishi Chūta of Ittō-ryū. The Naganuma branch, in contrast with the Otani branch, was said to favour jodan no kamae.

**Shindo Munen-ryū, founded by Fukui Hyōemon, was another prominent swordsmanship school in this period.

Do not use physical strength

Neither striking nor cutting requires physical strength. When an experienced drummer strikes a drum, he does so with crispness and the sound resounds cleanly.

Chuta sensei

Chūta sensei* said:

“When children are playing beside a well, and a child looks like they will fall in, any onlooker, no matter who, will be startled. This is the vital point in an engagement. Not only is it very interesting, it has a profound meaning.”

* Nakanishi Chūta, the first head of the Nakanishi line of Ittō-ryū.

Compare natural ability, hard work and enjoyment of training: of the three, the latter is most important for becoming skilled.*

Although a cow may walk slowly, its pace is fine. It will continue onwards for a thousand leagues, never resting nor taking its eyes from the path.

This is the way of strategy: to attack the heart is best; to attack city walls is worst. Battling with hearts is better than battling with soldiers.

- Zhuge Liang, Marquis of Zhongwu**

*These are regarded as the three necessary elements for mastery of an art.

**This is a quotation from the Chinese classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sangokushi, 三国志 in Japanese). It is advice given to Zhuge Liang by Ma Su during his campaign to subdue the southern tribes. When considering which strategy to employ against the city of Nanzhong, Zhuge Liang asked Ma Su’s advice, and was told that he should win the hearts of the people in the city rather than conquer them using military might.

Sources and further reading:

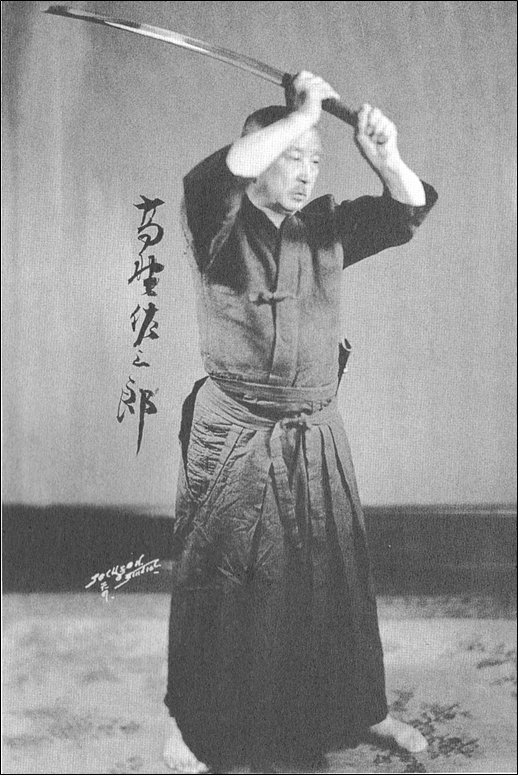

『剣道』 高野佐三郎〈著〉 島津書房発行 1982 ( 1915)

『兵法一刀流』 高野弘正〈著〉 講談社発行 1985

『一刀流極意』 笹森順造〈著〉 礼楽堂発行 1986 (1965)

『剣禅話』 山岡鉄舟〈著〉 高野登〈編訳〉 徳間書店発行 1971

『高野佐三郎 剣道遺稿集』 高野佐三郎〈著〉 堂本昭彦〈編〉 スキージャーナル株式会社発行 2007 (1989)

『剣道の発達』 下川潮〈著〉 梓川書房発行 1976 (1925)

『日本剣道史』 山田次郎吉〈著〉 一橋剣友会発行 1976 (1925)

『剣道五百年史』 富永堅吾〈著〉 百泉書房発行 1971

『増補大改訂 武芸流派大事典』 綿谷雪、山田忠史〈著〉 株式会社東京コピー出版部発行 1978