The importance of the Ittō-ryū school of kenjutsu in the history and development of kendo cannot be overstated. Generations of the most influential kendoka from the Bakumatsu to the early Showa eras (mid 19th-early 20th century) were students of this school. Much of modern kendo can find its origins in the teachings of Ittō-ryū.

The man who had perhaps the strongest influence on the formation of kendo, Takano Sasaburō, was an Ittō-ryū swordsman. The Ittō-ryū Book of Oral Recollections (Ittō-ryū Kikigaki, 一刀流聞書) was written by Sasaburō’s grandfather, Takano Mitsumasa, and is a record of the teachings of Mitsumasa’s Ittō-ryū instructor, Nakanishi Chūbei Tanemasa. Nakanishi Tanemasa was the head of the Nakanishi line of Ono-ha Ittō-ryū (today known as Nakanishi-ha Ittō-ryū) and taught a number of students who went on to become very famous in their own right, including Chiba Shūsaku (founder of Hokushin Ittō-ryū) and Asari Matashichirō Yoshinobu, whose successor taught Yamaoka Tesshū.

Clik here to view.

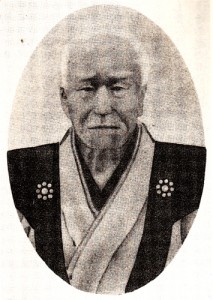

Takano Mitsumasa

The Ittō-ryū Book of Oral Recollections was written in the 19th century and was edited and published by Takano Sasaburo in the early 20th. As far as I am aware, this is the first ever English translation of the work to be published. Needless to say, this was not an easy piece to translate. The language used is archaic and often vague, and the text contains many references to inner teachings, densho, classical literature, folklore, and Buddhist and Confucian philosophy. As such, this translation very likely contains some errors. Any errors that do come to light after publication will be corrected in due course.

This translation project was initiated by Tsujimura Yosuke sensei, who wanted to make the work available to a wider audience. Some sections of this first instalment were originally translated by kenshi247.net contributor Leiv Harstad, and I have largely retained his work, as I failed to see how I could improve on it. As a number of people have put a lot of time and effort into this translation, I hope that people will respect that fact by linking to the original article on kenshi247.net rather than copying and pasting wholesale.

Finally, it should be noted that the original work is very much aimed at students of Ittō-ryū, and as such some parts may initially seem quite alien to modern kendo practitioners. However, I believe that this oft-overlooked treatise on classical swordsmanship is just as relevant to kendoka, and probably more so, than famous and widely-read works like Miyamoto Musashi’s Book of Five Rings. I hope you agree.

The Itto-ryu Book of Oral Recollections

Foreword

The Ittō-ryū Book of Oral Recollections (Ittō-ryū Kikigaki, 一刀流聞書) was written by my grandfather, Takano Mitsumasa. It records things said by his distinguished teacher of Ittō-ryū swordsmanship, Nakanishi Chūbei Tanemasa, while my grandfather was studying under his tutelage.

The book covers all areas of teaching, is very detailed, and contains many useful sections, but parts of it are repetitions of earlier sections or are incomprehensible to non-Ittō-ryū students. For this reason I have chosen to exclude sections that are out of line with today’s modern way of life, and publish only selected extracts.

- Takano Sasaburō

The sequence of training

You should train sword techniques obediently and sincerely, with no stiffness in the body or limbs.

In shiai [sparring with shinai], the body and hands should be kept relaxed and free from tension. In kata [using bokutō], you should pay close attention to the techniques, feeling and maai.

Moreover, after training in this way, practise with habiki [blunt blades] should be conducted as though you are engaged in combat using a sharp sword.

If you do not strictly train the body and harden the mind, then you will not be able to reach the level where you can train freely with habiki. Training with habiki is only one step away from a fight with real swords, so this training must be taken very seriously.

Maai

In your everyday practice, you should pay close attention to maai. Even when you have no opponent, you have maai. Although maai is of course affected by the length of your sword, it does not depend solely upon it.

Maai may be difficult to understand, but it is simply one’s own kamae. It is the distance from within which you can successfully strike and thrust.

When ippon-shōbu takes a long time, it is because combatants are taking care to establish correct maai without rashly entering their opponent’s striking range.

Maai with real swords

If you were to use a shinai of 2 shaku 3 sun 5 bu*, it would feel short for a shinai.

A bokutō of the above standard length feels longer than a shinai of the same length. Furthermore, if you use a habiki of this length, it will once again seem longer than the bokutō.

You should be aware of this when studying maai with a shinken.

* The same length as a standard Ittō-ryū bokutō (not including the tsuka) – approx. 71.2cm. The length of a adult’s modern kendo shinai is 3 shaku 9 sun (including the tsuka).

Clik here to view.

Ittō-ryū bokutō and shinai cut to the same length

How to act as uchidachi

When practising with a partner of greater skill, you should make it appear as if you are avoiding making contact, but in reality strike with full intent.

When practising with a partner of lesser skill, you should act as if you are really trying to strike them, whilst in fact you are avoiding making contact.

Various technical points

When the opponent steps forward with their right foot and cuts, you can strike them by moving to the right and cutting them from that side.

When facing an opponent who strikes powerfully, you should attack them first.

Proper use of the sword tip to pressure your opponent is good for your own training. However, it can be very unpleasant for your training partners.

If the opponent makes a shallow cut at your hands [i.e. with a short step in], your counter should be to evade by stepping back. This is because stepping back is a shallow [i.e. short range] motion.

If the opponent makes a deep cut [i.e. with a long step in], you should counter with kiriotoshi.* In this case, even if you try to evade, the opponent’s attack will still connect. Therefore, kiriotoshi should be used.

In shiai, even if your mind and sword are both correct, you may still be struck by the opponent. When the opponent initiates an attack, if you try too hard to utilise your own sword, it will stray to the side and the opponent can use this opportunity to successfully strike. This should be studied deeply.

While you are facing off against an opponent and applying pressure, it is bad to impatiently attack openings as soon as they present themselves. You should be patient, and keep firm pressure on the opponent, forcing them into making an attack. If you initiate an attack, you open yourself up to a strike from the opponent.

When your opponent is acting in a limp and unresponsive manner, if you adopt a similar facade without allowing your mind to become dull and languid, your opponent’s resolve will weaken. During a long bout, you should make your mind increasingly intense and focused. Then, while matching your actions with the opponent, you should keenly apply pressure with the sword tip.

* Kiriotoshi is the core principle that underpins Ittō-ryū technique, strategy and philosophy. It is a method of cutting ‘through’ an opponent’s strike, rendering it ineffective whilst delivering a strike of one’s own. Ittō-ryū’s kiriotoshi is different to what is commonly referred to as kiriotoshi in kendo today.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Avoid defensiveness

It is vital to look at the opponent as though you are trying to kill him with your glare. However, this does not mean looking at him with forceful eyes. Rather, you should brace your abdomen with a grunt, filling it with power.

The essential point is to communicate to the opponent that you have power in your abdomen with this grunt. Shouting at the opponent just means you will receive an attack. To merely hold your ground is to go on the defensive, and should be avoided.

Kakegoe

In shiai, kakegoe is used to indicate that you have found an opening to strike or thrust and are attacking it. Kakegoe should not be used to try and draw an opponent out; rather, it ought to be used when you have spotted an opening to strike or thrust. Simply shouting at your opponent is disrespectful and should be avoided.

Taiatari

During shiai, when you receive taiatari from your opponent, put power into your hips and make your body light, like a piece of floating driftwood. Remain flexible so that you can smoothly deflect your opponent to the left or right, diverting the force of their taiatari.

Regardless of if your opponent is large or powerful, you must not be in the least afraid of him. You must always believe you can best him.

Also, if attempting to knock your opponent down or get him under your control, you must remain calm and maintain the feeling that you can do as you please, whilst at the same time not letting your opponent feel that he can act freely.

Points of victory

Most people think only of cutting an opponent with their sword, and are completely ignorant of how to actually win in a duel. They are focused only on cutting the enemy.

It is dangerous to think only of cutting the opponent, while remaining oblivious of winning strategies such as controlling the opponent’s sword with harikomi [entering by slapping], osae [pressing] or makikomi [entering by winding]. After studying these points thoroughly, you will be able to attain victory.

There is an Ittō-ryū teaching*:

Do not think merely of striking the enemy

Protect yourself and openings will naturally appear

Like shafts of moonlight through a hovel’s tattered roof

*This teaching is a poem attributed to Itō Ittōsai Kagehisa, the founder of Ittō-ryū.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Strike large, counter small

During training, it is said that when striking, you should make a large strike, and when stopping an enemy’s strike, you must do so with a modest movement. If you do not, then when involved in a fight with live blades, anxiousness will naturally make your attacks smaller, and your movements to counter the strikes of your opponent will be too large.

Controlling your opponent with feeling

In shiai, if you utilise your sword tip freely, the opponent will unable to tolerate it. They will feel like they cannot act freely, and will feel very uncomfortable.

If you suppress your opponent with feeling in this way, and give them a little leeway in which to retreat, they will feel utterly powerless and will yield.

Respiration rhythm

Respiration rhythm [kokyū – this indicates a relationship between the respiration of both participants] is something you can come to understand through shiai.

When you strongly apply pressure from gedan your opponent will think you are going to thrust. If you then deliberately hold back, in the opponent’s ensuing moment of doubt you have an opening in which you can make a real thrust. This is the point of respiration rhythm.

Tanemasa sensei said:

“Watch a child sleeping. Think about how they are breathing, and how you are breathing. If your breath out does not match when the child is breathing in, you are not controlling the point of respiration.”

Don’t make others come to you

In your training, you should deliberately practise with difficult opponents. You should go to these people and request to do keiko with them. If you allow them to ask first, you may feel unable to do keiko with them, and wish you could postpone it until a later date. This will lend your opponent extra confidence and vigour, and you will end up feeling completely overwhelmed.

In your training, you should not try to make other people come to you. Even if you do not know anything about your opponent’s condition or technique, you should request to do keiko with them first.

Sources and further reading:

『剣道』 高野佐三郎〈著〉 島津書房発行 1982 ( 1915)

『兵法一刀流』 高野弘正〈著〉 講談社発行 1985

『一刀流極意』 笹森順造〈著〉 礼楽堂発行 1986 (1965)

『剣禅話』 山岡鉄舟〈著〉 高野登〈編訳〉 徳間書店発行 1971

『高野佐三郎 剣道遺稿集』 高野佐三郎〈著〉 堂本昭彦〈編〉 スキージャーナル株式会社発行 2007 (1989)

『剣道の発達』 下川潮〈著〉 梓川書房発行 1976 (1925)

『日本剣道史』 山田次郎吉〈著〉 一橋剣友会発行 1976 (1925)

『剣道五百年史』 富永堅吾〈著〉 百泉書房発行 1971

『増補大改訂 武芸流派大事典』 綿谷雪、山田忠史〈著〉 株式会社東京コピー出版部発行 1978