In part one of this series, I presented the first installment of a translation of The Ittō-ryū Book of Oral Recollections (Ittō-ryū Kikigaki, 一刀流聞書). This text was written in the 19th century by Takano Mitsumasa, based on the teachings of his kenjutsu sensei, Nakanishi Chūbei Tanemasa. Nakanishi Tanemasa was a hugely influential teacher, whose line of Ittō-ryū is credited with the innovation of shinai and bogu training that led to the development of kendo. Mitsumasa’s grandson Sasaburō, who edited and published this work in Japanese, was instrumental in codifying much of modern kendo and its pedagogy. Despite the huge historical significance of this work, it is not widely known of even within Japan, and to my knowledge, this is the first ever English translation to be published.

Part two continues below.

The two metsuke

When facing an opponent in shiai, the two metsuke* are as follows. For opponents in jōdan, you should watch the point from which they raise and lower their weapon [i.e. the hands]. Opponents in seigan will raise and lower their kissaki, attempting to hide their intent. When they are going to strike, they will raise the kissaki, and when they are going to thrust, they will lower it. Observing the kissaki, you should watch for when the opponent moves the sword in a real attack**. In this way, the truth will make itself known to you.

*‘Two Metsuke’ (futatsu no metsuke no koto, 二之目付之事) is an important teaching in Ittō-ryū and is the first recorded in the Jūnikajō Mokuroku (the first document of transmission issued to students of Ittō-ryū). On a basic level, it teaches that students should watch the hands and kissaki of the opponent. What is described above is one application of the concept. Takano Sasaburō’s own writings contain the same teaching – to look at the hands in jōdan, and at the kissaki in chūdan or gedan.

**Jitsu (実) in Japanese, meaning literally “truth.” Its counterpart is kyo (虚), “falsehood.” The ability to discern between these two is the ability to read the intentions of one’s opponent.

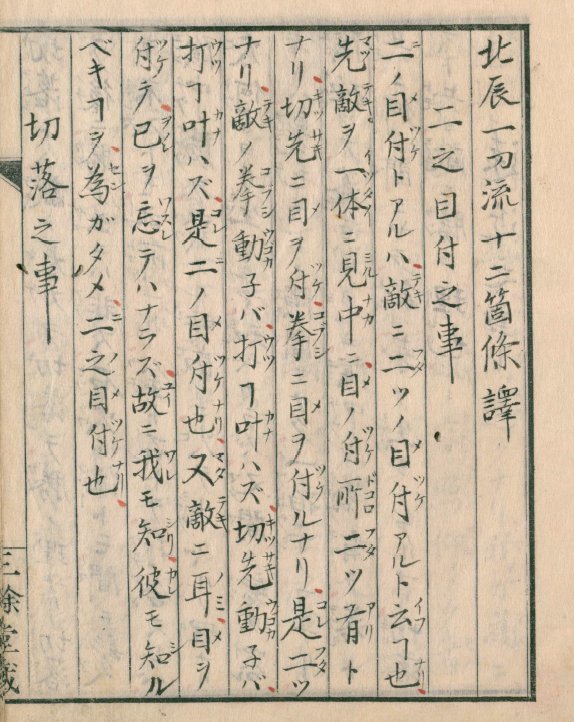

Clik here to view.

Extract from a Hokushin Itto-ryu document explaining the teaching ‘Two Metsuke’

Do not rely on spirit alone

The Kanaji Mokuroku* contains the line: “do not favour jōdan if you lack ability.” This means that if you attempt to use confidence and a strong spirit to overcome a lack of sufficient training in a technique, you will not be successful.

* The second of the major documents of transmission in Ittō-ryū.

Strong and weak points

Observe your sword and the opponent’s sword as a single entity, and pay attention to the strong points and weak points. Observing thus, you should put pressure on the weak point of the opponent’s sword using the strong point of your own weapon.

Sticking to the opponent

When sticking to your opponent* you should see them as being like sticky boiled rice, and be without stickiness yourself. When you are engaged with the opponent’s stickiness and attack naturally, even if you match with the opponent exactly, you will have points where you are stuck to the opponent and where you are not. This should be studied carefully.

* In Ittō-ryū, ‘sticking’ to the opponent’s sword is often referred to as sokui-tsuke. In some ways, this is similar in concept to tsubazeriai in kendo. However the position typically taken in Ittō-ryū is further out, vying for control of the centre with your sword ‘stuck to’ the opponent’s. There are a number of ways of writing sokui-tsuke but here the characters used are those for “quickly [prepared] rice.” More precisely, ‘sokui’ usually refers to rice that is boiled and then mashed to form a thick glutinous paste.

The three methods – so, gyo and shin

The three methods are as follows.* With sō you convey to the opponent, “that does not bother me, that is no good,” smother his attack and defeat him. With gyō you immediately show the opponent, “that is no good,” confront him aggressively and defeat him. With shin you immediately strike down the opponent.

*The “three methods” (note: this term appears in the English translation for clarity’s sake; the original text simply reads, “methods”) are known as sō (草), gyō (行) and shin (真) in Ittō-ryū and correspond to gosen no sen, senzen no sen and sensen no sen** respectively. Sō, gyō and shin have a much broader meaning than this in Ittō-ryū: in this case, however, they appear to refer to these three timings. The terms are originally taken from calligraphy, where shin denotes standard, precise characters (kaishotai), gyō denotes slightly looser, freer characters (gyōshotai) and sō denotes flowing script where the form of the characters is very free (sōshotai).

** These methods have different names in different schools of swordsmanship. Here they are defined as follows:

– Gosen no sen: you allow the opponent to move and then counter his attack.

– Senzen no sen: you strike in the instant the opponent begins his attack.

– Sensen no sen: you strike in the instant that the opponent thinks to attack, but before he can move.

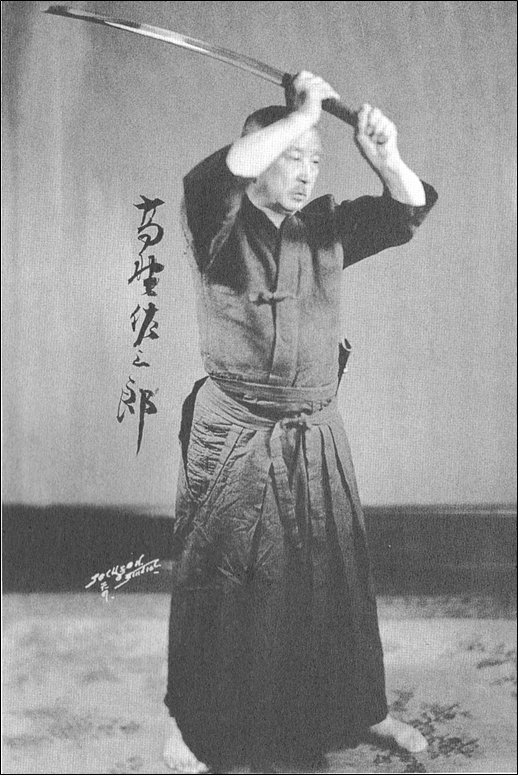

Swordsmanship and aging

If older swordsmen try to compete with younger opponents and make large attacks, their posture and grip will fail. This looks very poor. You should not care about being struck, and fence your opponent using correct technique. If you do not conceal physical frailties in this way, others will take notice and your status will suffer.

Older people may exert pressure with their sword tip but find their opponent’s mood and spirit does not become tense. In this case you should make an opening with a technique and thrust, strike men, or strike the left or right kote. In other words you should be able to adapt according to the opponent.

As you age, you will stop competing as much, and simply pay attention to surikomi [entering by sliding in], harikomi [entering by slapping] and uchikomi [entering with a strike], becoming acquainted with what you can and can’t do and only using the techniques you are capable with. This leads to areas of excess and deficiency.

At the age of sixty-two I competed in a shiai. Somehow, my younger opponent managed to knock me over with a thrust. Some people said that this was dangerous and that I should have been more cautious. While they may not find themselves knocked over with thrusts as I was, these types of people will be hit with strikes and thrusts at trifling moments. This is a ridiculous attitude which proves they know nothing about fighting with a sword.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Various teaching points

When working to raise the level of beginners, you should not worry about their footwork and so on, but teach them about the correct position of the sword, the correct method of kiriotoshi and so on, so they can smoothly and effectively perform these techniques. If you try to correct their footwork and body movement, they will pay too much attention to this. It will make them have a tension in their chest and be unable to use their hands smoothly. If you teach them to move their hands smoothly their footwork and body movement will naturally become smooth too.

There is a saying: a one-eyed monkey laughs at a monkey that sees clearly. A teacher who sees things in an unbalanced way will raise his students with the same biases, even though they may come to him without biases of their own.*

If your frame of mind is corrected, your physical posture will become correct also. If your physical posture becomes correct, the way you use your sword will become correct also.

People with the habit of raising their sword tip should correct their footwork and their sword tip will naturally lower.

People with stiff shoulders should correct their footwork and their shoulders will naturally become less tense.

People who become excessively fixated on observing the opponent’s state should correct their use of the sword tip, and their observation of the opponent will naturally become correct.

*Takano Sasaburō explains this concept in terms of a one-eyed monkey whose children have two eyes, but who keep one closed out of sympathy for their parent.

The vital point

People who are overly worried or concerned about a certain element of swordsmanship should stop thinking about that point in particular, and look to correct the basics underpinning that element.

A folding fan* is the same – the pin that holds the fan together is vital, and must reach through all the spines to secure them. This is why the pin of a fan is known as “the essential point.”**

*In Japanese, a folding fan (ōgi, 扇) is pronounced in the same way as ‘highest/secret teaching’ (ōgi, 奥義) – this metaphor is likely a play on words to indicate that the basics underpin everything, even the highest teachings.

**The word for the pin of a folding fan (kaname, 要) is also used to refer ‘the essential point’ of something. It is written with the character for ‘necessary.’

Act according to your opponent

If you are stronger, act weaker. If you are weaker, act stronger. This means that if your opponent is more skilled than you are, you should strike at them strongly and aggressively. If your opponent is less skilled than you are, you should allow them to strike at you.

The process of teaching

In swordsmanship, the process of teaching is as follows: first, teach students to relax and lose tension; when in the middle of their training, subject them to many hardships; finally, foster in them a courageous spirit.

Beginners should be taught to strictly adhere to the correct kamae for the start of a kata (be it gedan or seigan), the correct kamae for the end of a kata (be it gedan or jōdan), and the points where the kata begins and ends.

Meanwhile, although it is the most important part, the point of attaining victory should at first be ignored. Beginners should be made to focus strictly on the start and end of the kata. If from the start they are fixated only on the point of victory they will acquire bad habits.

To use an example, if an inexperienced person constructs a box, prepares tobacco or a makes a plate, even if they are very skilled, an expert will still be able to tell that it was made by an amateur.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Natural skill and correct methodology

In swordsmanship, including the swordsmanship popular today*, even if a novice has a lot of natural skill, they will not act in accordance with the correct methods of swordsmanship. They will therefore not be able to handle a real sword effectively.

* Possibly a reference to the spread in shinai competition.

Striking and cutting

When a senior practitioner cuts the opening in an opponent’s kamae with a blade, we call this cut a ‘strike.’ Today, people do not understand the meaning of this and try to imitate the cutting motion of a sword. This is of no use and does not aid in training.

Controlling the pace

When learning to play the flute, at first the calmer elements are taught. Later, the faster-paced elements are progressively introduced. Contrary to what one might expect, the timing of the calmer and more leisurely-paced elements is more difficult. In swordsmanship too, at first students should be made to engage at a comfortable pace. When using a real sword anyone will be able to strike instantly and decisively if they have learned to act without apprehension or delay.

Teacher and student

A teacher should know how to look at what a person is doing, thus grasp their mood, physical condition, method of striking with the sword, level of training, use of tenouchi and so on, and be able to correct the appropriate elements.

Regardless of how naturally skilled or unskilled someone is, and even if they fight very crudely, they may still be able to attain victory. Even if someone looks bad when training or if teaching them is extremely difficult, you should begin by carefully instilling in them the essential points of victory for a real sword fight.

If you learn from someone who is fundamentally bad, your development will be affected and you are likely to acquire bad habits.

On sparring with shinai

Since long ago, it has been stipulated in the kishōmon* that a student must be granted permission before they may participate in sparring using shinai. These days there is a trend for teachers to give all their students permission to participate in shinai training, and many in fact think that experience in shinai bouts is advantageous in a fight. However when I see students doing shinai practice, they look to me just like rank amateurs hacking away at each other. They do not show a desire to learn, and merely act according to their own whims.

In addition, the kishōmon of course absolutely forbids practicing with shinai in secret away from the dojo. However, many people commit this indiscretion. This current state of affairs calls for even more prudence by students.

*A kishōmon (起請文) is a written oath to adhere to the rules of a traditional school, signed by a student upon admission – in this case, the school in question is Ittō-ryū. This oath usually carries the penalty of celestial punishment from various deities for disobeying the rules.

Sources and further reading:

『剣道』 高野佐三郎〈著〉 島津書房発行 1982 ( 1915)

『兵法一刀流』 高野弘正〈著〉 講談社発行 1985

『一刀流極意』 笹森順造〈著〉 礼楽堂発行 1986 (1965)

『剣禅話』 山岡鉄舟〈著〉 高野登〈編訳〉 徳間書店発行 1971

『高野佐三郎 剣道遺稿集』 高野佐三郎〈著〉 堂本昭彦〈編〉 スキージャーナル株式会社発行 2007 (1989)

『剣道の発達』 下川潮〈著〉 梓川書房発行 1976 (1925)

『日本剣道史』 山田次郎吉〈著〉 一橋剣友会発行 1976 (1925)

『剣道五百年史』 富永堅吾〈著〉 百泉書房発行 1971

『増補大改訂 武芸流派大事典』 綿谷雪、山田忠史〈著〉 株式会社東京コピー出版部発行 1978